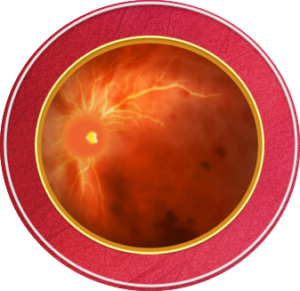

Pathophysiology

Retinal vein occlusions (RVO) are a major cause of vision loss and the second most common cause of retinal vascular disease, next to diabetes.1-6 These occlusions can be acute and chronic in nature, although chronic vein occlusion can be difficult to identify on clinical exam.3 Keep reading to learn about retinal vein occlusion classifications and symptoms.

Common presentations of RVO may include sudden, painless vision loss in one eye, as well as blurred vision or floaters.3,6-10 Although the majority of RVO are typically unilateral, 5%-6% of branch occlusions and 10% of central occlusions have demonstrated bilateral involvement. 7,11

The decreased blood flow in RVO resulting in the thrombosis of retinal veins has been described to be mediated by the following mechanisms:7

- External occlusion of the vein by a sclerotic central retinal artery (enclosed by the same sheath and secondary endothelial formation)

- Primary venous wall degeneration or inflammation

- Factors producing hemodynamic disturbances

Among the various risk factors for RVO, hypertension is significant and can cause a thickening or hardening of the overlying artery, inciting turbulent blood flow believed to promote venous thrombosis.1,3,12 This obstruction to blood flow increases venous pressure, potentially leading to vascular leakage, edema, hemorrhages and ischemia.5,12

The etiology of decreased vision in RVO is considered to be multifactorial, including macular edema, retinal ischemia, retinal hemorrhage, vitreous hemorrhage, neovascular glaucoma and retinal detachment.3,13 Of these, macular edema is the leading cause of vision loss in RVO due to the accumulation of fluid and swelling of the macula.7,14 Early detection and prompt treatment of vision-threatening complications, such as macular edema, provides the best visual outcomes.3

Classification of RVO subtypes

RVO can be classified according to anatomical location of the occlusion, such as the central retinal vein or its branch, as well as proximity to structures including the lamina cribrosa and optic nerve, and extent of retinal ischemia.3

Branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO)

Branch retinal vein occlusions are the most common type of RVO,5,7 occurring at the crossing points between veins and arteries sharing common connective tissue.3,5,12 BRVO most commonly occurs in the superior temporal quadrant12,14; this region usually has more arteriovenous (AV) crossings and therefore has an increased risk of vessel closure.1,3,18 Occlusions in this quadrant have also been associated with a greater degree of visual acuity loss as compared to alternate quadrants in BRVO.3 Additionally, about 20% of BRVO patients develop retinal neovascularization.3,12,14

Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO)

Central retinal vein occlusions account for 20% to 30% of vein occlusions5,7, and are associated with a higher rate of visual disturbances and poorer prognosis.13 CRVO is a result of a thrombosis of the central vein that typically occurs at or posterior to the lamina cribrosa, resulting in four quadrants of retinal hemorrhages.3,7,15 Subsequent macular edema is the leading cause of visual impairment.7

Hemiretinal vein occlusion (HRVO)

Hemiretinal vein occlusions are the rarest of all RVO’s and can occur in two ways. The first is when a branch of the central vein becomes occluded at or near the optic nerve; the second can be attributed to an anatomical variant where the central retinal vein has dual trunks.3 An occlusion in either trunk would result in about half of the retina to be affected.3,16,17

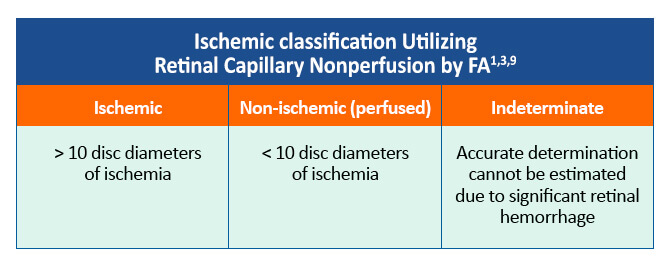

Ischemic vs non-ischemic RVO

These subtypes of RVO can be further classified as ischemic, nonischemic and indeterminate based on degree of fluorescein angiography (FA) retinal capillary nonperfusion.3 Reduced capillary perfusion and ischemia upregulate hypoxia-related factors, promoting expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and pro-inflammatory cytokines which are elevated in patients with RVO.12,13 This VEGF and cytokine production leads to new blood vessel growth which has a tendency to leak.12,13

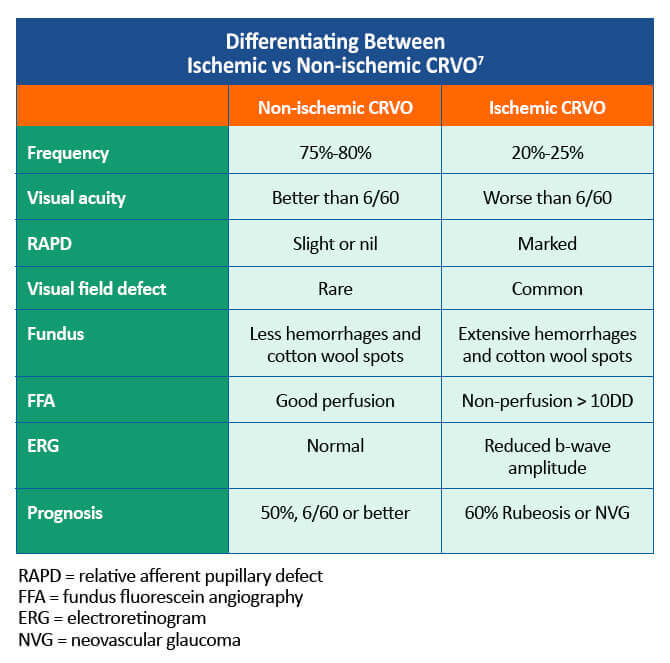

Ischemic CRVO can notably result in neovascularization of the iris or anterior drainage angle, leading to elevated intraocular pressure in a relatively short time span.3 This development of neovascular glaucoma is considered rare in BRVO.3 The following chart helps clinicians differentiate between non-ischemic CRVO vs ischemic CRVO.7

References

- Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE, et al. The epidemiology of retinal vein occlusion: The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2000;98:133-143. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1298220/

- Ehlers JP, Fekrat S. Retinal vein occlusion: Beyond the acute event. Surv Ophthalmol. 2011;56:281-299. https://www.surveyophthalmol.com/article/S0039-6257(10)00218-3/fulltext

- Jenkins T, Su D, Klufas MA. RVO Overview. Retina Today. April, 2018:40-58. https://retinatoday.com/articles/2018-apr/rvo-overview

- Cugati S, Wang JJ, Rochtchina E, et al. Ten-year incidence of retinal vein occlusion in an older population: The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:726-732. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaophthalmology/fullarticle/10.1001/archopht.124.5.726

- Stuart A. Untangling retinal vein occlusion. Eyenet Magazine. November, 2013. https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/untangling-retinal-vein-occlusion

- MacDonald D. The ABCs of RVO: a review of retinal venous occlusion. Clin Exp Optom. 2014:97:311-323. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/cxo.12120

- Morris R. Retinal vein occlusion. Kerala J Ophthalmol. 2016;28:4-13. https://www.kjophthal.com/text.asp?2016/28/1/4/193868

- American Society of Retina Specialists (ASRS). Branch retinal artery occlusion. 2016. https://www.asrs.org/patients/retinal-diseases/24/branch-retinal-vein-occlusion

- Evaluation of grid pattern photocoagulation for macular edema in central vein occlusion. The Central Vein Occlusion Study Group M report. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1425-1433. https://www.aaojournal.org/article/S0161-6420(95)30849-4/pdf

- American Society of Retina Specialists (ASRS). Central retinal vein occlusion. 2016. https://www.asrs.org/patients/retinal-diseases/22/central-retinal-vein-occlusion

- Rogers S, McIntosh RL, Cheung N, et al. The prevalence of retinal vein occlusion: Pooled data from population studies from the United States, Europe, Asia, and Australia. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:313-319.e1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2945292/

- Scruggs BA, Quist TS, Kravchuk O, et al. Branch retinal vein occlusion. Eyerounds.org. Last updated July 7, 2018. https://eyerounds.org/cases/274-branch-retinal-vein-occlusion.htm

- Jaulim A, Ahmed B, Khanam T, Chatziralli IP. Branch retinal vein occlusion: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, risk factors, clinical features, diagnosis, and complications. An update of the literature. Retina. 2013;33:901-910. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23609064/

- Goldman DS, CP Morley, MG.Heier, JS. Venous Occlusive Disease of the Retina: Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion. Ophthalmology. 4th ed: Elsevier Saunders; 2013; p. 526-534.

- Green WR, Chan CC, Hutchins GM, Terry JM. Central retinal vein occlusions: A prospective histopathologic study of 29 eyes in 28 cases. Retina. 1981;1:27-55. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1312193/pdf/taos00020-0396.pdf

- Chopdar A. Dual trunk central retinal vein incidence in clinical practice. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:85-87. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaophthalmology/article-abstract/634899

- Chopdar A. Hemi-central retinal vein occlusion. Pathogenesis, clinical features, natural history and incidence of dual trunk central retinal vein. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1982;102(pt 2):241-248. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6963518/

- Zhao J, Sastry SM, Sperduto RD, et al. Arteriovenous crossing patterns in branch retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:423-428. https://www.aaojournal.org/article/S0161-6420(93)31633-7/pdf

All URLs accessed December 9, 2020.